Integrative Psychotherapy Articles

Contributions of Gestalt Therapy to the Practice of Integrative Psychotherapy [1]

Richard G. Erskine

Abstract

Five philosophical foundations of Gestalt Therapy are described; they lay the foundation for the concepts of internal, external, and interpersonal contact. Contact is the central organizing principle of both Gestalt Therapy and a relationally-focused Integrative Psychotherapy. Two definitions of Integrative Psychotherapy are provided: 1) the internal, experiential process of making whole; and 2) the amalgamation of affective, cognitive, behavioural, physiological, and systems approaches to psychotherapy. The article concludes with the premise that an interpersonally contactful therapeutic relationship provides clients with an opportunity for healing, integration, and wholeness.

Keywords: Gestalt Therapy, Integrative Psychotherapy, Relational Psychotherapy, contact, existential philosophy

The premier issue of the Gestalt Review featured an editorial by Joseph Melnik that outlined six “underlying assumptions and organizing principles” of Gestalt Therapy (1997, p. 4). Included in that editorial were the concepts of field theory, phenomenology, dialogue, figure/ground, resistance as creative adjustment, and the therapeutic use of the Gestalt experiment. I agree with Melnik’s statement that it is a “difficult and challenging task to try to convey the breadth and scope of Gestalt therapy in a brief editorial” (1997, p. 7). Yet, I was surprised that he gave the theory of internal and external contact only a passing reference.

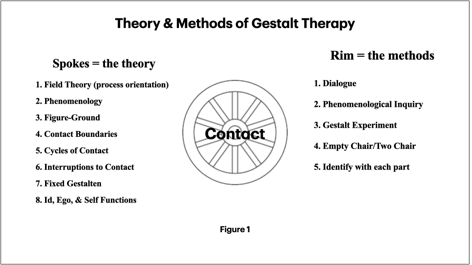

In my training with both Fritz and Laura Perls, as well as with Isidor From, they each emphasized “contact” as the central organizing principle of Gestalt Therapy. Metaphorically, the concept of contact is like the hub of a wagon wheel around which the other theoretical concepts radiate. Our psychotherapy methods, awareness-enhancing experiments, and therapeutic dialogue are represented by the wheel’s outer rim, and similar to a wheel, the spokes support and connect the hub to the rim. Field theory, phenomenological experience, presence in the moment, figure/ground formation, interruptions to contact, or resistance as creative adjustment are the supportive spokes. These theoretical concepts and assumptions are the significant constructs of Gestalt Therapy. In a 1967 lecture in Chicago entitled “Gestalt Therapy: Now and How”, Fritz Perls emphasized that “Contact is the central organizing principal of Gestalt Therapy”.

In Laura Perls’s teaching of Gestalt therapy, she referred to both her theoretical foundation and practice of psychotherapy as “applied existential philosophy” (L. Perls, 1977). Laura’s philosophical perspective was influenced by the work of several existential philosophers: Martin Heidegger’s (1976) concept of presence; Soren Kierkegaard’s (1936, 1941) emphasis on the centrality of subjectivity (Schacht,1973); the significance of Edmund Husserl’s (1931) views on phenomenological experience; Paul Tillich’s (1952) descriptions of the discovery of being; and Martin Buber’s (1958) commitment to establishing an I-Though relationship. Each of these existential philosophers was describing some aspect of either personal or interpersonal contact. Laura Perls demonstrated these intricate philosophy concepts in her therapeutic work through her continual respect for the client’s integrity and an invitation to meet in dialogue at the contact boundary between Self and Other. She focused on the therapist identifying and appreciating the client’s various attempts at making creative adjustment to the demands and losses in their life. Her therapeutic work emphasized the client’s experiencing both environmental support through an interpersonal therapeutic relationship, as well as gaining a visceral sense of self-support. To enhance self-support, Laura often drew attention to the restrictions in her client’s breathing and posture as she stressed the importance of physical movement.

In watching Fritz Perls work, I was impressed by the variety of ways in which he used, what he called, the “Gestalt experiment” – the client’s active discovery of both their self-imposed limitations and their exploration of new ways of being. Fritz’s use of the “empty-chair” experiment and the creation of “top dog – under dog” dialogues are two examples of his dynamic “here-and-now” therapeutic encounter that revealed to the client their interruptions to internal and external contact. Fritz’s use of Gestalt psychology concept of figure-ground formation was evident when he invited clients to enact each part of a dream in a “first-person” voice. Although Fritz often described individuals’ reluctance to change as “creative adjustment”, he was not patient with the amount of relational support and preparation time that some clients require. Fritz’s therapeutic work was exciting and growth-producing for many of us, but his style of conducting psychotherapy was neither dialogical nor relational.

Isidor From, as the principal in the faculty of the New York Institute for Gestalt Therapy, focused his teaching on the significance of internal and external contact, the various interruptions to contact (retroflection, confluence, introjection, projection, and egotism) and the cycles of contact (fore-contact, contact, full-contact, post-contact). From’s teaching about the practice of Gestalt therapy emphasized the use of a contactful interpersonal relationship that facilitated the client’s full awareness and integration of three primary functions of the self: id-function (physiological sensations); ego-function (identifying me & not me); and personality-function (social presentation). In his practice of Gestalt therapy, Isidor From emphasized the significance of the client’s phenomenological experience and the growth producing aspects of interpersonal dialogue.

The Gestalt Therapy concepts of phenomenological experience, figure-ground formation, mutual influence (field theory), and functions of the self are all facets of contact-making. Both habitual interruptions to contact (such as retroflection, introjection, or projection), and fixed Gestalten (rigidly held patterns of behaviour and beliefs about self, others, and the quality of life) each represent a lack of full internal contact, and as a result, a disruption in external contact. These interruptions to contact impede awareness internally, externally, and interpersonally. These concepts provide the theoretical foundation for a contact-orientated Gestalt Therapy. They also provide some of the core concepts in a Relationally-focused Integrative Psychotherapy

Contact: internal, external, interpersonal

In Gestalt Therapy, the concept of “contact” is defined as the means whereby a person’s bodily and emotional sensations, physical and relational needs, and phenomenological experiences are integrated into a full sense of Self. Contact involves the full awareness of internal sensations, affect, needs, sensory-motor activity, thoughts, and memories with a rapid shift to full awareness of external events as registered by each of the sensory organs. With full contact, both internally and externally, there is a continual integration of sensations, experiences, and perception. It is through full contact that people have a sense of being alive, an awareness of both continuity and novelty of experience, and a clarity of self-in-relationship with others. The coalescing of internal, external, and interpersonal contact is the medium through which archaic self-stabilizing patterns and fixed Gestalten can be dissolved; whereby disallowed affect, previously unacknowledged needs, and emotionally disruptive experiences can be integrated into a cohesive and lively sense of self-in-relationship.

Contact is the touchstone of relationship; it is what makes relationship possible. The essence of our being human is inextricably tied up in the ways we relate to others. We are conceived and born within a matrix of relationships, and we live our lives in the world that is inevitably and consequently populated by other humans, both externally and internally via fantasies, expectations, introjections, and memories.

The philosophical concept of “contact” is not only about awareness of internal sensations and external stimuli, the term “contact” also refers to the interpersonal meeting of people; it constitutes the building blocks of relationship. Although the term is not used in the book, Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth of the Human Personality (Perls, Hefferline & Goodman, 1951), the colloquial use of the words “interpersonal contact” describe a quality of transaction between two individuals: the full awareness of both one’s self and the others, as exemplified in an authentic and sensitive encounter — a meeting of the Other with both presence and an I-Thou perspective (Buber, 1958; Yontef, 1993; Hychner & Jacobs,1995). Interpersonal contact is what Laura Peals meant when she described her practice of Gestalt Therapy as “applied existential philosophy” (1977).

The existential philosophical foundation of Gestalt Therapy also provides guiding principles for a relationally-focused Integrative Psychotherapy – a psychotherapy that fosters respect for the client’s integrity through attending to and valuing the psychological function of the client’s archaic patterns of self-support, attempts at creative adjustment, and the homeostatic functions of their fixated beliefs about Self, Others, and their quality of life. Each of these fixated beliefs, these interruptions to contact, was originally an attempt solve ruptures in relationships (disruptions at the contact boundary) and to gain self-support in situations where the relationship with others was devoid of interpersonal contact. (Erskine, 2021; Erskine et al., 2023).

Interpersonal dialogue between client and therapist provides the therapeutic context in which the client can explore his or her own feelings, needs, memories, and perceptions. Interpersonal contact between client and therapist begins to be possible when the therapist is fully present: when the therapist is continually aware of their own inner processes and external behaviours, is cognizant of the boundary between self and client, and his keenly observant of the client’s psychodynamics (Erskine, 2024). Interpersonal contact is enhanced through respectful phenomenological inquiry about the client’s thoughts, feelings, memories, behaviours, and physiological reactions; it fosters the client’s sense of awareness of their moment-by-moment inner experience. The client’s capacity for internal contact is increased through the therapist’s responses that acknowledge and validate the client’s phenomenological experience.

A Relationally-focused Integrative Psychotherapy

The integrative aspect of Integrative Psychotherapy has two distinct meanings. Primarily, it refers to the process of making whole through facilitating each client’s capacity to re-own disavowed affects, identifying previously desensitized body sensations, relaxing archaic ways of self-stabilization and self-protection, relinquishing script-beliefs (fixed Gestalten), and re-engaging with the world and relationships with full contact. The therapeutic focus of Integrative Psychotherapy is on the internal integration of the client’s personality: helping the client to assimilate and harmonize internal fragmentations of their sense of Self and to establish meaningful relationships. Through internal integration, it becomes possible for people to have the capacity to face each moment openly and freshly, without the protection of preformed opinion position, attitude, or expectation.

The term integrative also refers to the integration of theory, the melding of affective, cognitive, behavioural, physiological, and systemic approaches to psychotherapy. Integrative Psychotherapy makes use of many theoretical perspectives: Gestalt Therapy, Client Centred Therapy, Transactional Analysis (particularly ego-state and script theory), breathing and body-oriented therapies, family systems therapy, as well as psychoanalytic self-psychology, and object relations theory. The concepts and various methods of these theoretical perspectives are utilized within the realm of human development, in which each phase of life presents heightened developmental tasks, need sensitivities, crises, and opportunities for new learnings (Erskine, 2019). The guiding principle as to whether a theoretical construct or therapeutic methods is “integratable” is that of relationship.

If a theory or method is integratable in a Relationally-focused Integrative Psychotherapy depends on whether or not it incorporates the concept that interpersonal relationships are central to life (Erskine & Moursund, 2022). Ronald Fairbairn (1952) instituted a significant change in the theory and practice of psychoanalysis when he declared that people are born relationship-seeking from the beginning of and throughout their lives. He described how the need for relationship (contact with another) constitutes the primary motivating experience of human behaviour. Relationships are the source of that which gives meaning and validation to the Self.

John Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) expanded this concept with the idea that the quality of relationship with significant others in early childhood forms unconscious patterns from which all experiences of Self-with-Others emerge. Bowlby proposed that healthy psychological development emerged from the mutuality of both the child’s and caregiver’s reciprocal enjoyment in their physical connection and affective relationship.

Relationships are established and maintained through contact. These concepts about the significance of interpersonal relationship are central to the practice of psychotherapy because “an effective healing of psychological distress and relational neglect occurs through a contactful therapeutic relationship — a relationship in which the psychotherapist values and supports vulnerability, authenticity, and interpersonal contact.” (Erskine, 2021, p. 212)

Contact

A person cannot have full contact with internal sensations, feelings, needs, thoughts, and memories, while at the same time, pushing some of those internal events out of awareness. As a result, contact with the external world, with other people, becomes impaired because meeting another person authentically requires a full acknowledgement of one's own self. Since relationships between people are based on internal and external awareness, prolonged contact disturbance causes a disruption in the person’s ability to form and maintain relationships. The result is an ever-increasing fragmentation and a growing inability to integrate new experiences.

Gestalt therapy has given us a useful way to understand how our needs shift and change in normal life. It uses the concept of “figure-ground” relationships: a vast complex of potential needs that lie in the background of our experiencing. And at any given moment, one of those needs is “figure” (Perls, 1947; Perls, Hefferline & Goodman, 1951). We move ahead, not so much propelled by instinctive drives (as Freud believed), but by acting purposely to satisfy the shifting patterns of our own needs. Those needs include what will allow us to survive physically; but, they also include the psychological needs for stimulation, for contact with Self, and with Others, for creating meaning and predictability, and for relationship.

When working with the client’s interruptions to contact the therapist’s continual self-monitoring is essential. Drawing from the philosophical influence of Heidegger (1976), Tillich (1952), and Buber (1958), a question that I frequently ask myself is: “What is the effect of my inner affect and behaviour on the client?” When I take at least partial responsibility for my client’s interruptions to contact, I create an atmosphere that enhances contact-in-relationship. My ongoing inquiry about the client’s experience of the effect of my feelings, behaviour, value system, or orientation towards the psychotherapy, provides a relationship-oriented basis for both Gestalt Therapy and Relationally-focused Integrative Psychotherapy. When contact-in-relationship is the focus of our psychotherapy, the client can make ever-increasing internal contact with memories, needs, desires, feelings, fantasies, and the process of meaning-making. With full internal contact, the client can communicate their internal awareness to another who is involved and fully present. An interpersonally contactful therapeutic relationship provides an opportunity for healing, integration, and wholeness (Erskine et al., 2023, p.ix).

Phenomenological Inquiry and Acknowledgement

The client’s increasing awareness of the existence of their interruptions to contact is the initial focus of a contact-oriented psychotherapy. Some clients begin psychotherapy with a lack of awareness of their needs and desires, with disavowed affect, inconsistent memory of their history, a desensitization of physiological sensations, and/or an insensitivity to the effect of their behaviour on others. The psychotherapist’s use of a respectful phenomenological inquiry is intended to enhance the client’s awareness of their internal processing of affect, physical sensations, fantasy, meaning–making, and perceptions. The possibility of internal contact is enhanced through the therapist’s use of phenomenological inquiry. Some examples are:

- "What's happening in your body at this moment?"

- “What are you remembering?”

- “How do you make sense of that experience?”

- "What are you imagining?”

In each of these phenomenological inquiries, the effectiveness of the inquiring is in the client’s discovering and contacting an internal aspect of Self – such as, feelings, memory, fantasy, or relational-needs.

Phenomenological inquiry is not just about gathering facts of the client’s life, but rather, inquiring about his or her subjective experience, and providing the opportunity to have that experience acknowledged and validated by an interested other. With such an effective inquiry, the client gains an ever-increasing awareness of their internal processes. Inquiry is usually 90% for the client’s self-discovery and 10% as a guide to the psychotherapist.

When we genuinely listen and empathetically respond to what the client says, we provide a valuable form of acknowledgment. Acknowledgement may be a simple nod of the head that signals to the client, “I am with you: I'm attentive to what you’re saying”. Acknowledgement is often in the form of our next inquiry, where we reflect back to the client what they have just said as we form the next phenomenological inquiry. Acknowledgement may also include respectful confrontations that bring to the client’s awareness discrepancies between affect and behaviour: what is said now, and what was previously said (i.e., “You say that you yearn to talk to your father, yet you describe avoiding each opportunity to talk to him”). Such acknowledgement, if done in a non-shaming way, often leads to the client’s increasing self-discovery. Acknowledgement is often followed by further phenomenological inquiry (“Do you experience any discrepancy?”). Or an inquiry regarding the client’s perception of the therapist's involvement (“What do you experience happening within you when I point out what appears to me to be a discrepancy?”).

Historical Inquiry and Validation

Just as phenomenological inquiry reveals the existence of internal and external interruptions to contact, the origins of contact disturbances are often revealed through historical inquiry. Historical inquiry involves questions about: what happened to the client; the developmental age when a disturbance in relationship may have occurred; and who was involved. A sensitively constructed historical inquiry will often provide information about the nature of previous relationships, the client’s vulnerability, and the relational-needs that were unmet. When we empathically respond to our client’s discovering their psychological history, we provide validation of their internal experience. Historical inquiry often involves factual questions whereas phenomenological inquiry is about the client’s internal, subjective experience. As we shuttle between phenomenological and historical inquiry, the client will often reveal the absence of need-fulfilling relationships, as well as the hope that “someone will be responsive to my needs”.

Although we cannot verify what we have not observed, the therapist can validate that the client’s attempts at affect stabilization, fantasy, or "weird" behaviours have significant psychological functions, such as predictability, identity, continuity, and affect stabilization. These homeostatic functions are attempts at managing disruptions in relationship while also serving as an unconscious request for a reparative relationship.

Coping Inquiry and Normalization

An important dimension of inquiry is through the psychotherapist’s respectful exploration into the client’s style of coping and how they have managed stress, interpersonal conflict, loss, or abuse. The intent of inquiry into the client’s style of coping is to facilitate the client’s awareness of the physiological survival reactions, implicit conclusions, and explicit decisions that they may have made when living with stress, neglect, or in relational conflicts. In such an inquiry, the psychotherapist facilities the client in being cognizant of how these old patterns of coping may continue to affect their current life by inhibiting their spontaneity and limiting their flexibility in problem solving, health maintains, and in their relationships with people.

Normalization is composed of transactions that provide an alternative view to the client’s childhood ways of understanding stressful situations. For example, a client continually berated himself with “It’s my fault that my parents were always fighting”. Another client talked about how she never protested against her father’s constant criticism and physical punishment of her brother. With the first client I responded with, “It is common for a child to blame themself for conflicts between their parents in order to maintain a good image of their parents”. With the second client I said, “Of course you would remain quiet to avoid further criticism and possible punishment. That was a smart thing to do.” Both of these responses to the client help to normalize their thoughts and behaviour and pave the way for them to discover what they needed in the relationship with their parents. Normalization of the client’s old patterns of coping opens the possibility for the client to change behaviour.

Inquiry about the client’s coping style illuminates – for both the client and therapist – the stabilizing, regulating, and reparative functions that the client has been managing alone. Our phenomenological inquiry and acknowledgement, historical inquiry and validation, as well as our inquiry into the client’s patterns of copying and normalization all provide an interpersonally contactful relationship where the various relational-functions can be identified and explored within the therapeutic relationship. In a relationally-focused psychotherapy, we provide both the validation and normalization that fosters the client’s full awareness of how they have managed the difficult situations in their life.

Therapeutic Involvement:

Involvement is an essential component of an authentic, person-to-person therapeutic relationship. Therapeutic involvement is the expression of the philosophical principles reflected in Marin Heidegger’s concept of presence, in Paul Tillich’s focus on the continuous discovery of being, and in Martin Buber's compassionate perspective on the sacred uniqueness of the other. To paraphrase Laura Perls, therapeutic involvement is the manifestation of existential philosophy.

Therapeutic involvement emerges from the psychotherapist having a genuine interest in the client’s intrapsychic and interpersonal worlds and then communicating that interest through attentiveness, patience, and respectful inquiry. Our involvement is reflected in our acknowledgment, validation, and normalization of what the client presents, as well our willingness to be known. When we are fully involved in the therapeutic process, we allow ourselves to be emotionally aroused and to share judiciously our internal experience with the client because therapeutic involvement has more to do with being than doing.

Therapeutic involvement begins with the psychotherapist’s commitment to the client’s well-being, an unwavering awareness that the client, and what they need in a therapeutic relationship, is most important. This commitment is the bedrock that makes an authentic involvement possible. The involved psychotherapist is with-and-for the client, fully contactful, honest and willing to put energy and effort into helping clients achieve their goals. When we are fully committed to the client’s welfare, our involvement enriches the client’s vitality and helps them form a secure sense of self. Involvement is what makes relationship vibrant: two people exchanging ideas and feelings, each challenging and enhancing the authenticity of the other.

Therapeutic involvement is also about the intersubjective interplay between us, the dance of interpersonal contact. The important aspects of psychotherapy are embedded in the distinctiveness of each interpersonal relationship, not in what we consciously do as a psychotherapist, but in the quality of how we are when in relationship with the other person. Our attitudes and demeanour, the qualities of our interpersonal relationship, and the authenticity of our intersubjective connections are central in creating an effective psychotherapy. A central premise of a relationally-focused integrative psychotherapy is that effective healing of our clients’ psychological distress and relational neglect occurs through a contactful therapeutic relationship – a relationship in which the psychotherapist values and supports vulnerability, authenticity, and interpersonal contact (Erskine, 2015).

Conclusion

As we integrate the various therapeutic concepts of Integrative Psychotherapy, such as phenomenological inquiry, acknowledgement, validation, and therapeutic involvement, we rely on the philosophical principles expressed in the writings of several authors who have also influenced Gestalt Therapy. Martin Buber has provided a compassionate perspective on the sacred uniqueness of the other person. Martin Heidegger’s concept of presence lays the foundation for full contact in our therapeutic involvement with clients. Paul Tillich and Soren Kierkegaard’s focus on the continuous discovery of being emphasizes the importance of both subjectivity and intersubjective dialogue, while Edmund Husserl’s views on the significance of subjective experience provide the impetus for engaging in phenomenological inquiry. These existential philosophical foundations of Gestalt Therapy provide the foundation on which relationally-focused Integrative Psychotherapy is based.

Author:

Richard G. Erskine, Ph.D. has served as the Training Director of the Institute for Integrative Psychotherapy in New York City and Vancouver, Canada since 1976. Originally trained in client-centered therapy, Richard studied Gestalt therapy with Fritz Perls, Laura Perls, and Isador From. He is a certified clinical Transactional Analyst and a licensed Psychoanalyst who has specialized in psychoanalytic self-psychology and object-relations theory. In1972, while a professor at the University of Illinois he gave the first in a series of lectures on the integration of affective, behavioral, cognitive, and physiological aspects of psychotherapy. He is Professor of Psychology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Deusto University, Bilbao Span and the author of several books and professional articles on the theory and methods of psychotherapy. His web site is www.IntegrativePsychotherapy.com

Appreciation:

“Thank you” to David Forrest, from Gestalt UK, for the illustrative diagram of the theory and methods of Gestalt Therapy. David’s website is: www.gestaltuk.com/

Reference

BOWLBY, J. (1969). Attachment. Volume I of Attachment and Loss. Basic Books.

BOWLBY, J. (1973). Separation: Anxiety and Anger. Volume II of Attachment and Loss. Basic Books.

BOWLBY, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness and Depression. Volume III of Attachment and Loss. Basic Books.

BUBER, M. (1958). I and Thou. (Trans. R.G. Smith) Scribner.

ERSKINE, R. G. (2015). Relational Patterns, Therapeutic Presence: Concepts and Practice of Integrative

Psychotherapy. London: Karnac Books.

ERSKINE, R. G. (2019). Child Development in Integrative Psychotherapy: Erik Erikson’s First Three Stages.

International Journal of Integrative Psychotherapy, 10: 11-34.

ERSKINE, R.G. (2021). Early Affect Confusion: Relational Psychotherapy for the Borderline Client. nScience

Publishers.

ERSKINE, R. G. (2024). Countertransference: An Integrative Psychotherapy Perspective.

International Journal of Psychotherapy. 28,1. pp. 47-61

ERSKINE, R. G. & MOURSUND, J.P. (2011). Integrative Psychotherapy in Action. London: Karnac

Books. (Originally published by Sage Publications, 1988 and by The Gestalt Journal Press, 1998).

ERSKINE, R.G. & MOURSUND, J.P. (2022). The Art and Science of Relationship: The Practice of Integrative

Psychotherapy. Phoenix Publishing.

ERSKINE, R.G., MOURSUND, J.P. & TRAUTMANN R.L. (2023). Beyond Empathy: A Therapy of Contact-in-Relationship. Rutledge Mental Health Classic Editions. Original work published 1999.

FAIRBAIRN, W.R.D. (1954). Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality. Basic Books.

HEIDEGGER, M. (1976). Basic Writings from Being and Time (1927) to The Task of Thinking (1964). Harper & Row

HUSSERL, E. (1931/1982) Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy. Trans. F. Kersten. Kluwer Academic Publishers/.

HYCNER, R. & JACOBS, L. (1995). The Healing Relationship in Gestalt Therapy. The Gestalt Journal Press.

KIERKEGAARD, S. (1936). Philosophical Fragments or A Fragment of Philosophy. (Trans. David F. Swenson). Princeton University Press.

KIERKEGAARD, S. (1941). (Concluding Unscientific Postscript. (Trans. David F. Swenson and Walter Lowrie). Princeton University Press.

MELNICK, J. (1997). Welcome to Gestalt Review: An Editorial. Gestalt Review, 1:1-8.

PERLS, F.S. (1947). Ego, Huner, and Aggression. George Allen & Unwin.

PERLS, F.S. (1967). Gestalt Therapy: Now and How. Lecture, Chicago City Collage, Chicago, Illinois, September 28, 1967

PERLS, F.S., HEFFERLINE, R.F. & GOODMAN, P. (1951). Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality. Julian Press

PERLS, L. (1977). Theory and Practice of Gestalt Therapy. Keynote address, European Association of Transactional Analysis, July 8, 1977. Seefeld, Austria.

SCHACHT, R. (1973). Kierkegaard on 'Truth Is Subjectivity' and 'The Leap of Faith’. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 2:3, p. 297-313.

TILLICH, P. (1952). The Courage to Be. Yale University Press.

YONTEF, G.M. (1993). Awareness, Dialogue, and Process. Gestalt Journal Press

-----------

German

German English

English Spanish

Spanish French

French Italian

Italian Portuguese

Portuguese Russian

Russian